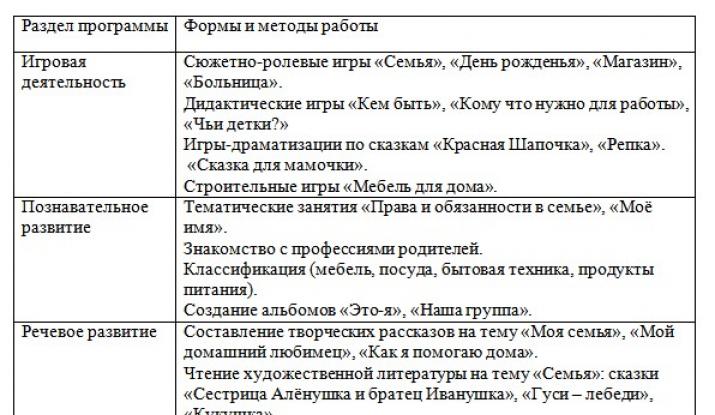

(decorative fabrics, carpets, tablecloths, etc.). It makes it possible to separately manage each thread of the warp or a small group of them. Created in 1804.

Encyclopedic YouTube

1 / 3

✪ Jacquard - LIVE, China

✪ DORNIER jacquard loom

✪ Picanol looms

Subtitles

History

Named after the French weaver and inventor Joseph Marie Jacquard.

Application

The jacquard machine makes it possible, when a pharynx is formed on a loom, to separately control the movement of each thread or a small group of warp threads and to produce fabrics whose rapport consists of a large number of threads. Using a jacquard machine, it is possible to produce patterned dress and decorative fabrics, carpets, tablecloths, etc.

Description

The jacquard machine has knives, hooks, needles, a plank, frame cords and a perforated prism. The warp threads, made into the eyes of persons (galevs), are connected to the machine using arcade cords threaded into a dividing board for uniform distribution along the width of the machine. Knives fixed in a knife frame reciprocate in a vertical plane. The hooks located in the area of \u200b\u200baction of the knives are grabbed by them and rise upwards, and the warp threads rise upwards through the frame and arcade cords, forming the upper part of the throat (the main overlap in the fabric). Hooks brought out of the range of the knives are lowered down along with the frame board. The lowering of hooks and warp threads occurs under the influence of gravity weights. The lowered warp threads form the lower part of the pharynx (weft weaves in the fabric). Hooks from the area of \u200b\u200baction of the knives are displayed with needles, which are affected by a prism having oscillating and rotational movements. A cardboard is made up of a prism, consisting of individual paper cards that have cut-out and not-cut places against the ends of the needles. Meeting the cut-out place, the needle enters the prism, and the hook remains in the area of \u200b\u200bthe knife’s action, and the not-cut place of the card moves the needle and disconnects the hook from the interaction with the knife. The combination of the cut and not cut places on the cards allows for a quite definite alternation of raising and lowering the warp threads and the formation of a pattern on the fabric.

A striking example of a computer-controlled machine, created long before the advent of computers. The punched card is typed in a binary code: there is a hole, there is no hole. Accordingly, some thread rose, some did not. The shuttle throws a thread into the formed pharynx, forming a two-sided ornament, where one side is a color or texture negative of the other. Since to create even a small-sized pattern, about 100 or more weft threads and an even larger number of warp threads are required, a huge number of perforated cards were created, which were connected into a single ribbon. Scrolling, she could occupy two floors. One punched card corresponds to one procid shuttle.

Jacquard fabric

coarse fabrics of any kind of fiber produced on jacquard looms and going to the production of bedspreads, tablecloths, etc .; named J.M. Jacquard.

Joseph Marie Jacquard

Joseph Marie Jacquard (1752–1834)

french inventor. Born in Lyon in the family of a silk spinner. He inherited a small workshop from his father, but soon went bankrupt. In 1790, the goal was to restore the loom built 50 years earlier by Jacques de Vaucazan. It was one of the first examples of an automatic loom. The French Revolution temporarily interrupted the work of Jacquard. He fought in the ranks of the Republican army, but after the victory he set to work again. In 1801 he designed the machine, for the control of which punch cards were used; later he improved the machine by combining punch cards into an endless ribbon, which made it possible to weave large canvases and carpets. The French government became interested in the invention. Jacquard began to pay money for every loom made of his design. In 1812, 11 thousand Jacquard machines were operating in France. They began to appear in other countries. The use of automatic looms in 1820 caused a textile boom in Europe.

Subsequently, Charles Babbage used punched cards similar to those used by Jacquard in order to create an automatic counting device.

see also Ada.

safety Shaving Blade, the world's first disposable product. The name is named after K.K. Gillette.

King Camp Gillette

King camp gillette

american inventor and entrepreneur. Born in Font du Lac (Wisconsin). In 1871, his family lost all their property in a big fire in Chicago. Gillette was forced to become a salesman, selling hardware. While sharpening the blade of a dangerous razor, he came up with a safe replaceable blade (a steel plate with two sharp edges) and a safety razor (a clip of this blade equipped with a handle). The invention was met with skepticism - after all, the blades could not be re-sharpened. In 1903, only 51 razors and 168 blades were sold, but by the end of 1904, 90 thousand razors and 12 million 400 thousand blades. Until 1931, Gillette was president of the company he created for the production of razor blades, and left real management in 1913, devoting himself to promoting his social views. He was a Utopian socialist, author of several books and articles; believed that competition was wasteful, and called for the creation of a planned society controlled by technocrats. In 1910, he unsuccessfully offered US President Theodore Roosevelt to create a "global corporation" in Arizona (which had not yet become the US state) and become its president. Gillette himself agreed to allocate $ 1 million for this endeavor.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the French weaver and inventor Joseph-Marie Jacquard invented a new technology for industrial patterning of fabrics. Now such fabrics are called jacquard, and his machine - jacquard. Jacquard's invention makes it possible to obtain a variety of lighting effects on the surface of the fabric, and in combination with different colors and material of the threads, beautiful, soft transitions of tones and sharply defined contours of patterns, sometimes very complex (ornaments, landscapes, portraits, etc.). Jacquard is used for sewing dresses, outerwear, furniture fabrics, curtains, as well as for the manufacture of lanyards, badge tapes and other promotional materials (stripes, chevrons, labels, promotions).

Joseph Jacquard was born on July 7, 1752. in Lyon. His father owned a small family weaving industry (two looms), and Joseph also began his career as a child at one of the many weaving factories in Lyon. But this hard and unsafe work did not appeal to him, and the future inventor went to study and work in a bookbinding workshop.

But Jacquard was not destined to become an outstanding inventor in bookbinding or printing. Soon, his parents die, and he inherits looms and a small piece of land. As a result of several unsuccessful business projects, Joseph loses most of his father’s inheritance, but at the same time he is fond of the engineering problem of improving the loom.

Despite the rapid development of weaving in France, the possibilities themselves  looms were very limited. Monochrome fabrics or colored stripes were produced in droves. Fabrics with embroidered patterns were still made by hand. Jacquard wanted to improve the loom so that it was possible to make patterned fabrics in an industrial way.

looms were very limited. Monochrome fabrics or colored stripes were produced in droves. Fabrics with embroidered patterns were still made by hand. Jacquard wanted to improve the loom so that it was possible to make patterned fabrics in an industrial way.

By 1790, Jacquard created a prototype of the machine, but active participation in revolutionary events in France did not allow him to continue working on improving his invention. After the revolution, Jacquard continued his design searches in a different direction. He invented a machine for weaving nets and in 1801 he took him to an exhibition in Paris. There, he saw Jacques de Vaucanson's loom, which back in 1745 used a perforated roll of paper to control the weaving of threads. What he saw prompted Jacquard to a brilliant idea, which he successfully used in his loom.

To manage each thread individually, Jacquard came up with a punched card and an ingenious mechanism for reading information from it. This made it possible to weave fabrics with patterns predefined on the punch card. In 1804, the invention of Jacquard received a gold medal at the Paris exhibition, and he was granted a corresponding patent. The final industrial version of the jacquard machine was ready by 1807.

In 1808, Napoleon I awarded Jacquard a prize of 3,000 francs and a right to a prize of 50 francs each  operating in France machine of its design. By 1812, more than ten thousand jacquard looms worked in France. In 1819, Jacquard received the Cross of the Legion of Honor.

operating in France machine of its design. By 1812, more than ten thousand jacquard looms worked in France. In 1819, Jacquard received the Cross of the Legion of Honor.

Joseph Marie Jacquard died in 1834 at the age of 82. In Lyon in 1840, a monument was erected to him. The Jacquard loom allowed not only industrial weaving of fabrics with complex patterns (jacquard), but also became the prototype of modern automatic looms.

The Jacquard machine is the first machine to use a punch card in its work.

Already in 1823, the English scientist Charles Babaj tried to build a computer using punch cards. At the end of the 19th century, an American scientist built a computer and processed the results of the 1890 population census on it. Punched cards in computer technology were used until the middle of the twentieth century.

For many years, punched cards served as the main carriers for storing and processing information. In our minds, a punch card is firmly associated with a computer occupying an entire room, and with a heroic Soviet scientist making a breakthrough in science. Punch cards - the ancestors of floppy disks, disks, hard drives, flash memory. But they did not appear at all with the invention of the first computers, but much earlier, at the very beginning of the 19th century ...

Falcon's machine tool Jean-Baptiste Falcon created his machine on the basis of the first such machine designed by Basil Bouchon. He was the first to invent a system of cardboard punch cards connected in a chain.

Alexander Petrov

On April 12, 1805, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and his wife visited Lyon. The country's largest weaving center in the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries was badly damaged by the Revolution and was in a deplorable state. Most factories went bankrupt, production stood still, and the international market was increasingly filled with English textiles. Wanting to support the Lyon masters, in 1804 Napoleon placed a large order for cloth here, and a year later he arrived in the city personally. During the visit, the emperor visited the workshop of a certain Joseph Jacquard, the inventor, where the emperor was shown an amazing machine. The masses mounted on top of an ordinary loom tinkled with a long ribbon of perforated tin plates, and a silk cloth with an exquisite pattern stretched, spinning onto a shaft. At the same time, no master was required: the machine worked on its own, and even an apprentice could well serve it, as the emperor was explained.

1728. Falcon machine. Jean-Baptiste Falcon created his car on the basis of the first such machine designed by Basil Bouchon. He was the first to invent a system of cardboard punch cards connected in a chain.

1728. Falcon machine. Jean-Baptiste Falcon created his car on the basis of the first such machine designed by Basil Bouchon. He was the first to invent a system of cardboard punch cards connected in a chain.

Napoleon liked the car. A few days later, he ordered the transfer of Jacquard's patent for a weaving machine to public use, and the inventor himself to put an annual pension of 3,000 francs and the right to receive a small, 50 francs, deduction from each loom in France on which his car stood. However, as a result, this deduction amounted to a significant amount - by 1812, 18,000 looms were equipped with a new device, and in 1825 - already 30,000.

The inventor lived the rest of the days in abundance, he died in 1834, and six years later, the grateful citizens of Lyon erected a monument to Jacquard in the very place where his workshop had once been. Zhakkarova (or, in the old transcription, “jacquard”) the car was an important brick in the foundation of the industrial revolution, no less important than the railway or steam boiler. But not everything in this story is simple and cloudless. For example, the "grateful" Lyons, who later honored Jacquard as a monument, broke his first unfinished machine tool and attempted his life several times. And the truth is that he didn’t invent the car at all.

1900. Weaving shop. This picture was taken more than a century ago in the factory floor of a weaving mill in Darwell (East Ayrshire, Scotland). Many weaving shops look to this day - not because factory owners spare money for modernization, but because the jacquard looms of those years still remain the most versatile and convenient.

1900. Weaving shop. This picture was taken more than a century ago in the factory floor of a weaving mill in Darwell (East Ayrshire, Scotland). Many weaving shops look to this day - not because factory owners spare money for modernization, but because the jacquard looms of those years still remain the most versatile and convenient.

How the car worked

To understand the revolutionary novelty of the invention, it is necessary in general terms to present the principle of operation of a loom. If you look at the fabric, you can see that it consists of tightly interwoven longitudinal and transverse threads. In the manufacturing process, longitudinal threads (warp) are stretched along the machine; half of them are attached to the “remise” frame through one, the other half to the same frame. These two frames move up and down relative to each other, spreading the warp threads, and the shuttle pulling the transverse thread (ducks) back and forth into the formed pharynx. The result is a simple canvas with threads interwoven through one. The frame-remizok can be more than two, and they can move in a complex sequence, raising or lowering the threads in groups, which is why a pattern forms on the surface of the fabric. But the number of frames is still small, rarely when it is more than 32, so the pattern is simple, regularly repeating.

There are no frames at all on the jacquard loom. Each thread can be moved separately from the others with the help of its rod with a ring. Therefore, on the canvas you can weave a pattern of any degree of complexity, even a picture. The sequence of movement of the threads is set using a long looped card punch card, each card corresponds to one shuttle pass. The card is pressed to the "reading" wire probes, some of them go into the holes and remain stationary, the rest are recessed with the card down. The probes are connected to the rods that control the movement of the threads.

Complicated canvases knew how to weave before Jacquard, but only the best masters could do it, and the work was hellish. A jerking worker climbed inside the machine and, at the command of the master, manually raised or lowered individual warp threads, the number of which was sometimes in the hundreds. The process was very slow, required constant attention, and errors inevitably occurred. In addition, the re-equipment of the machine from one complexed canvas to another work sometimes stretched for many days. The machine tool of Jacquard did the work quickly, without errors - and himself. The only difficult thing now was to fill in punch cards. It took weeks to produce one set, but once produced cards could be used again and again.

Predecessors

As already mentioned, the "smart machine" was not invented by Jacquard - he only modified the inventions of his predecessors. In 1725, a quarter of a century before the birth of Joseph Jacquard, the first such device was created by the Lyon weaver Basil Bouchon. Bushon's machine was controlled by perforated paper tape, where each row of the shuttle corresponded with one row of holes. However, there were few holes, so the device changed the position of only a small number of individual threads.

The next inventor who tried to perfect the loom was called Jean-Baptiste Falcon. He replaced the tape with small sheets of cardboard tied around corners in a chain; on each sheet, the holes were already arranged in several rows and could control a large number of threads. The Falcon machine was more successful than the previous one, and although it was not widely used, the master managed to sell about 40 copies throughout his life.

The third one who undertook to bring the loom to mind was the inventor Jacques de Vaucanson, who in 1741 was appointed inspector of silk weaving manufactories. Vaucanson worked on his machine for many years, but his invention was unsuccessful: a device too complex and expensive to manufacture could still control a relatively small number of threads, and a plain fabric did not pay for the cost of the equipment.

1841. Weaving workshop of Karkill. A woven pattern (made in 1844) depicts a scene that occurred on August 24, 1841. Monsieur Karkilla, the owner of the workshop, presents to the Duke d'Omale the canvas with a portrait of Joseph Marie Jacquard, woven in the same way in 1839. The subtlety of the work is incredible: the details are smaller than on engravings.

1841. Weaving workshop of Karkill. A woven pattern (made in 1844) depicts a scene that occurred on August 24, 1841. Monsieur Karkilla, the owner of the workshop, presents to the Duke d'Omale the canvas with a portrait of Joseph Marie Jacquard, woven in the same way in 1839. The subtlety of the work is incredible: the details are smaller than on engravings.

Good luck and failures of Joseph Jacquard

Joseph Marie Jacquard was born in 1752 on the outskirts of Lyon in a family of hereditary Canuts - weavers who worked with silk. He was trained in all the intricacies of the craft, helped his father in the workshop, and after the death of his parent inherited the matter, but he was far from engaged in weaving. Joseph managed to change many professions, was tried for debt, married, and after the siege of Lyon he left as a soldier with a revolutionary army, taking his sixteen-year-old son with him. And only after the son died in one of the battles, Jacquard decided to return to the family affair.

He returned to Lyon and opened a weaving workshop. However, the business was not very successful, and Jacquard became interested in invention. He decided to make a machine that would surpass the creations of Bouchon and Falcon, would be quite simple and cheap, and at the same time could make a silk canvas, not inferior in quality to a hand-woven. At first, the designs that came out from under his hands were not very successful. The first Jacquard machine, which worked as it should, did not make silk, but ... fishing nets. In the newspaper, he read that the Royal Royal Society for the Support of the Arts had announced a competition for the manufacture of such a device. He never received a prize from the British, but he was interested in his brainchild in France and was even invited to an industrial exhibition in Paris. It was a landmark trip. Firstly, they paid attention to Jacquard, he got the necessary connections and even got the money for further research, and secondly, he visited the Museum of Arts and Crafts, where Jacques de Vaucanson's loom was located. Jacquard saw him, and the missing details fell into place in his imagination: he understood how his car should work.

With his developments, Jacquard attracted the attention of not only Parisian academics. Lyon weavers quickly realized the threat posed by the new invention. In Lyon, whose population was barely 100,000 by the beginning of the 19th century, more than 30,000 people worked in the weaving industry - that is, every third resident of the city was, if not a master, then an employee or an apprentice at a weaving workshop. An attempt to simplify the fabrication process would have deprived many of the work.

The incredible precision of the Jacquard machine

The well-known painting “The visit of the Duke of O'Mal to the weaving workshop of Mr. Karkill” is not an engraving at all, as it might seem, - the picture is completely woven on a machine equipped with a jacquard machine. Canvas size - 109 x 87 cm, the work was done, in fact, by the master Michel-Marie Karkilla for the company Didier, Petit and Sea. The process of mis en carte - or programming the image on punch cards - lasted many months, with several people doing it, and the production of the canvas took 8 hours. A tape of 24,000 (more than 1,000 binary cells each) punch cards was a mile long. The picture was reproduced only by special orders; several canvases of this type are known that are stored in various museums around the world. And one portrait of Jacquard so woven in this way was commissioned by Charles Babbage, Dean of the Department of Mathematics, University of Cambridge. By the way, the duke d'Omal depicted on the canvas is none other than the youngest son of the last king of France, Louis Philippe I.

As a result, one beautiful morning a crowd came to the workshop of Jacquard and broke everything that he was building. The inventor himself was severely punished to leave unkind and engage in craft, following the example of his late father. Contrary to the exhortations of the brothers in the workshop, Jacquard did not give up his research, but now he had to work secretly, and he finished the next car only by 1804. Jacquard received a patent and even a medal, but he was careful not to sell smart machines on his own, and on the advice of the merchant Gabriel Detille, he asked the emperor to transfer the invention into the public ownership of the city of Lyon. The emperor granted the request, and awarded the inventor. You know the ending of the story.

Punch Card Age

The very principle of the jacquard machine - the ability to change the sequence of the machine by loading new cards into it - was revolutionary. Now we call it the word "programming." The sequence of actions for the jacquard machine was set in a binary sequence: there is a hole - there is no hole.

1824. Difference machine. Babbage The first experience with Charles Babbage's construction of an analytical machine was unsuccessful. The bulky mechanical device, which is a combination of shafts and gears, calculated quite accurately, but required too complicated maintenance and highly skilled operator.

1824. Difference machine. Babbage The first experience with Charles Babbage's construction of an analytical machine was unsuccessful. The bulky mechanical device, which is a combination of shafts and gears, calculated quite accurately, but required too complicated maintenance and highly skilled operator.

Soon after the jacquard machine became widespread, perforated cards (as well as perforated tapes and discs) began to be used in a variety of devices.

Shuttle machine

At the beginning of the XIX century, the main type of automatic weaving device was a shuttle machine. It was arranged quite simply: the warp threads were stretched vertically, and the bullet-shaped shuttle flew between them back and forth, dragging the transverse (weft) thread through the warp. From time immemorial the shuttle was dragged by hands, in the XVIII century this process was automated; the shuttle "shot" on one side, was accepted on the other, unfolded - and the process repeated. The pharynx (the distance between the warp threads) for the shuttle span was provided with the help of a bird-weaving ridge, which separated one part of the warp threads from the other and lifted it.

But perhaps the most famous of these inventions - and the most significant on the way from the loom to the computer - is the "analytical machine" of Charles Babbage. In 1834, Babbage, a mathematician inspired by Jacquard's experience with punch cards, began work on an automatic device to perform a wide range of mathematical problems. Prior to that, he had a bad experience building a “difference machine,” a bulky 14-ton monster filled with gears; The principle of processing digital data using gears has been used since Pascal's time, and now punch cards should replace them.

1890. The tabulator of Holleritis. Herman Hollerith's tabulating machine was built to process the results of the 1890 All-American Census. But it turned out that the capabilities of the machine go far beyond the scope of the task.

1890. The tabulator of Holleritis. Herman Hollerith's tabulating machine was built to process the results of the 1890 All-American Census. But it turned out that the capabilities of the machine go far beyond the scope of the task.

The analytical machine contained everything that exists in a modern computer: a processor for performing mathematical operations ("mill"), memory ("warehouse"), where the values \u200b\u200bof variables and intermediate results of operations were stored, there was a central control device that also performed input functions output. Two types of punch cards were to be used in the analytical machine: large format, for storing numbers, and smaller - software. Babbage worked on his invention for 17 years, but could not finish it - there was not enough money. The current model of Babbage’s “analytical machine” was built only in 1906, so the direct predecessor of computers was not she, but devices called tabulators.

A tabulator is a machine for processing large amounts of statistical information, textual and digital; information was entered into the tab using a huge number of punched cards. The first tabulators were designed and created for the needs of the American census office, but soon they were used to solve a variety of problems. From the very beginning, one of the leaders in this field was the company of Herman Hollerith, the man who invented and manufactured the first electronic tabulation machine in 1890. In 1924, Hollerita was renamed IBM.

When the first computers replaced the tabs, the principle of control using punch cards remained here. It was much more convenient to load data and programs into the machine using cards, rather than switching numerous toggle switches. Here and there punch cards are used to this day. Thus, for almost 200 years, the main language in which a person spoke with “smart” machines remained the language of punch cards.

The article “Loom, great-grandfather of computers” was published in the journal Popular Mechanics (

Joseph Marie Jacquard - the famous inventor of the XVII - XIX centuries. His main invention - an industrial method of fabric production - is of great importance for modern computer science and helped to develop the first prototype of electronic

Joseph Marie Jacquard: A Brief Biography

J. M. Jacquard (1754 - 1834) is known for inventing an industrial loom. The future French inventor was born in Lyon in 1752. As the son of a weaver, Joseph Jacquard was trained by a bookbinder and could work at a foundry - an enterprise engaged in the creation of metal plates with fonts and ink for printing.

However, after the death of his father, his son inherited his business and became a weaver. Joseph lost his son during the French Revolution, then Lyon fell, the revolutionaries had to leave the city and go underground. Returning to his native Lyon, Jacquard undertook any work and repaired many different looms in an attempt to distract from his grief.

In 1790, Joseph Marie Jacquard made the first attempt to create an industrial machine. Lyon at that time, as now, was a vibrant industrial area of \u200b\u200bFrance, through it passed many trade routes from ports deeper into the continent. The inventor gets acquainted with autonomous machines Jacques de Vaucanson, who opened his own production in the city. Witty and elegant mechanical toys in the form of animals and people struck Jacquard and helped to correct the shortcomings of his own invention.

Recognition of the merits of Jacquard by contemporaries

In 1808, work on a loom was completed. Having become an empire, France could no longer satisfy the needs of a huge, constantly howling army with the help of manual labor. The need for fabrics was vital, so the industrial machine was very welcome.

The achievements of Joseph Marie Jacquard were noted by Napoleon I, the weaver was laid a considerable pension from the state, and the right was given to collect deductions in his favor from each machine of France of the invented design. In 1840, the noble inhabitants of Lyon erected a monument in honor of the inventor who glorified the city.

Jacquard

Joseph's machines and the resulting fabric were called jacquard in honor of the creator. Jacquard was unusually widely used both in past times and now. From this fabric make outerwear, unusually beautiful dresses, as well as covers and upholstery for furniture.

Fabric rapports contain a minimum of 24 threads that weave out unusually complex and beautiful patterns. When creating materials, you can combine them, which makes it possible to create very interesting effects on finished products. Making home interiors in the Rococo and Baroque style is almost impossible without chic jacquard curtains, upholstery and pillows.

The complexity of producing reports made the work of the masters and the finished fabric incredibly expensive, only aristocrats and rich people could afford such luxury. Dresses and dresses from jacquard are still striking in the beauty of their pattern; for kings and close aristocrats in the manufacture of gold and silver threads were used in weaving.

The tight weave and intricate patterns create a unique relief and tapestry effect. The thicker the threads, the denser and stronger the fabric itself. Thin and soft jacquard is used for outfits, rough and dense - for upholstery of furniture and covers, or even when creating carpets.

Jacquard loom

The main difference between the machine, invented by Jacquard, was that the position of the thread in the pattern did not depend on its parity. Each thread in the pattern had its own weaving program. Plain paper cards — perforated prisms — controlled the position of the threads. Punch cards could control up to 100 threads and had the appropriate length.

The prisms of the report were sewn into one working tape and changed as necessary by the machine operator. The device itself is incredibly simple and yet effective. It necessarily includes a board-frame for the fabric and its cords, a large set of hooks and knives, needles and program cards for each thread. All threads pass through the holes of a long board for even distribution. Hooks cling to the spindle and can carry it beyond the action of the blades. Warp threads are pulled at the bottom of the device in a horizontal direction.

Needles move through slots in software maps. They have cut and not cut areas, the operator can specify the oscillating and rotational movements of the prisms along which the control needles move. The uncut areas of the cards divert the needles and remove the hook from the spindle, while the active needle forces the hook to move the desired thread.

Elegant solution

The jacquard loom is an outstanding example of a computer controlled machine invented before the term “binary code” appeared. Punched cards change the position of the needle from “active” to “not active” and embody the principle of operation of all computer technology known to all modern computer scientists - “zero / one”.

Joseph’s punch cards were used for their intended purpose much later, and his invention was the first programmable device and for a long time determined the direction of further development of industrial equipment around the world.

What did the inventor not guess?

The invention of the industrial loom was a real breakthrough not only for contemporaries, but also brought closer the creation of autonomous computer technology by subsequent generations. Joseph Marie Jacquard apparently did not even know the real meaning of what he had invented.

However, it was simple cardboard weaving control tables that laid down the principle of programming production lines in the future. Joseph Marie Jacquard can be called The practical achievements of the inventor are really unique, because the theoretical foundations of the concept of the algorithm and the description of the simplest programming principles were made only during the Second World War. The scientist developed his abstract machine for cracking secret military ciphers, like the code of the famous Enigma.