Sitting today in front of computer screens, we don’t think about the fact that we received all these “electronic amenities” not only thanks to successes in the fields of electronics, mathematics, cybernetics and chemistry. No matter how strange it may sound, the development of the textile industry played an important role in the emergence of what we call a “computer”.

Throughout the history of the existence of the species homo sapiens, man has come up with various ways to simplify his work. Such an area of \u200b\u200bactivity as the manufacture of clothing was no exception. The first mention of looms dates back to the fifth millennium BC. e. These primitive mechanisms were a simple vertical frame on which warp threads were stretched. The weaver had to hold a large shuttle with thread in his hands and bind the base. It was a very time-consuming work, as the threads had to be sorted by hands, they were often torn, and the fabric was very thick. A little later a horizontal loom loom appeared in Egypt. Behind such a frame, a person worked while standing, while the words “stand” and “machine tool” came from the word “stand”. Be that as it may, the work of the weaver still remained difficult.

Only in the 18th century did mechanical looms begin to appear. In 1733, the English cloth-maker John Kay invented a mechanical shuttle for a hand-loom. The invention made it possible not to hand over the shuttle manually, and also made it possible for the weaver to produce wide fabrics on the machine without the help of an apprentice. In 1771, the English city of Cromford began operating a spinning mill of the large industrialist and inventor Edmund Arkwright, the machines in which were driven by a water wheel. Encouraged by a visit to the Arkwright factory, another English inventor Edmund Cartwright received a patent for a foot-operated mechanical loom in 1785 and organized a weaving mill in Yorkshire with 20 such machines.

The rapid development of technical thought in the field of weaving in the XVIII century, of course, greatly simplified the work of weavers, but, nevertheless, many issues remained unresolved. For example, the manufacture of fabrics with complex patterns was a real problem. The production of such fabrics was only possible for the best craftsmen, and they did not work alone. Inside the machine there should have been an apprentice who, at the command of the master, manually raised and lowered warp threads, the number of which could be in the hundreds. Such a process was extremely time-consuming and slow, it required enormous concentration, and for mistakes that happened quite often, one had to pay a lot of time. In addition, the time-consuming process was the conversion of the machine from the production of one pattern to another, which took several days.

Of course, the inquiring mind of a person could not ignore this problem. Based on the task, two requirements were formed: the new mechanism should reproduce the movements of the weaver and his apprentice according to a predetermined scenario; he must have some kind of storage device in order to store a sequence of commands for the manufacture of certain patterns. Many inventors tried to cope with this task, among which were Basil Bouchon, Jean-Baptiste Falcon, Jacques Vaucanson. Their mechanisms partially satisfied the formulated requirements, but for various reasons the work was not brought to its logical end, and their machines were not widespread in the weaving industry. The only one who succeeded was the French inventor Joseph Jacquard. His creative years came at a time when two revolutions raged - the Great French and Industrial. Everything changed, and Jacquard became one of the sources of these changes.

Jacquard Biography

Joseph Marie Charles (Joseph Marie Charles), later known by the name Jacquard (Jacquard) - a nickname assigned to his family, was born July 7, 1752 in the French city of Lyon. He was the fifth of nine children of Jean Charles, a weaving master who worked in a brocade workshop, and his wife Antoinette Rivier. Like many sons of weavers of that time, Joseph Marie did not attend school, as his father needed him as an apprentice. He learned to read only at the age of 13, thanks to his half-brother Barrett, a very educated person. Joseph's mother died in 1762, and his father in 1772. After the death of his parents, Jacquard inherited his father’s apartments and his workshop, equipped with two looms. In 1778, he himself became a master of weaving and a silk merchant. In the same year, he married the rich widow of Claudia Boichon. In this marriage in 1779 they had the only son Jean Marie.

| Joseph Marie Jacquard |

Over the years, Jacquard made several dubious transactions, as a result of which he went into debt and lost all his inheritance and part of his wife’s property. In the end, Claudia stayed with her son in Lyon, where she worked in a straw hat factory, and Joseph went to France in search of good luck. He managed to work as a lime killer and as a laborer in quarries, and as a result, returned home in the late 1780s.

At the beginning of the French Revolution, Joseph and his son took part in the unsuccessful defense of Lyon against the forces of the National Convention. When the city fell, they managed to escape. After that, under false names, they joined the Revolutionary Army. In one of the bloody battles, Jean Marie was tightly hit by a bullet, and having lost the meaning of life, Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1798 returned to Lyon. After treatment at the hospital, he undertook any feasible work - repairing looms, sewing fabrics, bleaching straw hats, driving carts. This continued until 1799, when he decided to do automation of looms. This venture, in the end, brought him fame.

Inventive activity

Extensive experience working with machine tools as an apprentice, weaver and adjuster made it clear to Jacquard that fabric production, although it is a rather complicated and meticulous task, on the one hand, on the other hand, is just a routine process with a lot of repetitive actions. He believed that the embroidery of complex patterns can be automated, that is, reduced to a minimal set of simple movements. In addition, he was aware of the successes and failures of his compatriots in the field of automation of weaving.

As a result, Jacquard conceived a system whose operation depended on the sequence of holes on special hard plates. Today we would call them punch cards. It should also be noted that similar prototypes of punch cards were implemented on the machines of Bouchon, Falcon and Vaucanson, but their devices could either control a small number of threads or were too complicated and expensive to manufacture and maintain. Taking into account all the shortcomings of his predecessors, Jacquard made punch cards with many rows of holes, this allowed the machine to operate with a large number of threads. He also simplified the mechanism for feeding punch cards into the reader of the machine, making them a long closed tape. Moreover, each card corresponded to one shuttle pass. The reading mechanism of the machine was a set of probes that were connected to the rods that control the movement of the threads. When the card passed, the probes pressed against it and remained motionless, while if there were holes on the path of any probes, the probes fell into them and lifted the corresponding warp threads, thereby forming the upper part of the pharynx, i.e. the main overlap in the fabric. The lowering of warp threads occurred under the influence of gravity weights. The lowered warp yarns formed the lower part of the pharynx or weft weaves in the fabric. Thus, the correct sequence of cut and not cut places on punch cards made it possible to carry out the necessary alternation of raising and lowering the warp threads, which ultimately formed the desired pattern.

Jacquard made the first model of his own loom in 1801. The machine, however, was not intended for embroidering complex patterns on fabrics, but for weaving fishing nets, as Joseph Marie learned from the newspaper that the British Royal Society for the Support of the Arts had announced a competition for the manufacture of such a mechanism. As a result, he simultaneously exhibited his brainchild at competitions of the Royal Society for the Support of Arts and the Society for the Promotion of Crafts and Arts in France. In the UK, his machine was not awarded any prize, but in his own country, in France, the invention attracted the attention of interested parties, and as a result, in 1804, Jacquard was invited to Paris, where in the workshops of the Conservatory of Arts and Crafts he should was to complete the construction of his mechanism. There, Jacquard discovered a collection of cars from Vaucanson’s office, among which there was a sample of a patterned machine. Having carefully examined in practice the principle of its action, Joseph Marie made some improvements to his own development.

A year later, Jacquard and his invention were awarded the attention of Napoleon himself. The emperor of France was well aware of the importance of textile production for the country's economy, and therefore placed a large order for cloth in Lyon, a city that has long been famous for its weavers. In April 1805, during his visit to the city of Napoleon, his wife Josephine visited the workshop of Jacquard, where he was shown a miracle machine. Having appreciated the efficiency and ease of maintenance of this mechanism, the emperor granted Jacquard a pension of 3,000 francs and the right to receive deductions of 50 francs from each machine operating in a French manufacture. Napoleon ordered the patent for invention to be transferred to public use. So Jacquard lost intellectual property, but acquired a solid income at that time and state support. In addition, the scale of the distribution of Jacquard's machines grew by leaps and bounds, which increased his profit and, as a result, made him one of the richest people in the city. By 1812, more than 11,000 such looms were operating in France, and despite attempts by the French government to keep the technology secret, similar looms began to appear in other countries.

Although the invention brought fame and fame to Jacquard, among his compatriots there were those who directly condemned him and even switched to open confrontation. Of course, they were Lyon weavers, angry that the mass introduction of new weaving machines into production deprived many of them of their jobs. And for a city in which weaving is leading, it becomes especially critical and explosive. Even before Jacquard gained wide fame, some weavers figured out how dangerous a new machine could be for them, and once, breaking into his workshop, they broke all the mechanisms there. The inventor himself was repeatedly beaten, but, no matter what, secretly continued to work on his brainchild until he received the fortune, fame and approval of the supreme authority.

The rest of the days, Jacquard lived in abundance and died in the quiet town of Uhllen, located in the southeast of France near the Alps. Six years later, the grateful inhabitants of Lyon erected a monument in his honor on the very spot where his workshop was located.

The influence of Jacquard's invention on the further development of technical thought

The principle of “programming” mechanisms through punch cards, the basis of the Jacquard loom, was revolutionary for its time. The widespread use of such machines prompted other inventors and craftsmen to think about using this principle in their designs.

The pioneer of Russian cybernetics Semen Nikolaevich Korsakov (1787-1853) in 1832 filed with the Imperial Academy of Sciences an application for the invention of a “machine for comparing ideas”. This "machine" was a series of devices that were combined into a kind of information retrieval system. Using modern terms, it could be called a "tool for creating and processing databases." The main carriers of information in these devices were punch cards, which were stored in special file cabinets and mechanically sorted by certain signs. Korsakov first met punch cards two decades before filing this application. He participated in the Patriotic War of 1812, and then in the Overseas campaign against Napoleon of 1813-1814, during which he traveled to Paris with the Russian army, where he saw a working Jacquard machine with a program “written” on punch cards that was pre-built into it. Returning to Russia, Korsakov became the head of the statistical department, and the routine work with statistical materials prompted him to create a number of devices using punch cards as information carriers. Korsakov's mechanisms, unfortunately, were not widely used, although he himself successfully used them to compile databases in the course of his work.

In 1834, the English mathematician Charles Babbage (Charles Babbage, 1791-1871) began work on an automatic device for solving a wide range of mathematical problems - the "analytical machine". Prior to that, he had unsuccessful experience in building a "difference machine", a huge and complex mechanism that operated with a large number of gears. Now, as Babbage planned, punch cards were supposed to replace gears. To do this, he specially traveled to Paris to study the principle of "programming" Jacquard machine tools through punch cards. Babbage was not able to finish the car due to the complexity and lack of financial resources, however, the principles laid in its foundation contributed to the further development of computer technology.

In computer technology, punch cards have gained practical utility and value thanks to the American engineer and inventor Herman Hollerith (1860-1929). In 1890, for the needs of the US Census Bureau, he developed a tabulator - a mechanism for processing statistical data with punch cards as information carriers. In 1911, the Tabulating Machine Company, a company founded by Hollerith, was renamed International Business Machines (IBM). Punched cards were successfully used in computer technology until the second half of the last century, until they were replaced by more advanced storage media.

As for jacquard machines, they are still used in the manufacture of high-quality products. The main difference from the machines of two centuries ago is the use of a computer and an image scanner. Today, designers using a scanner transfer the pattern that needs to be applied to the fabric to the computer, then a program for the machine with the necessary sequence of operations is compiled from the received image. Naturally, such a process of setting the pattern algorithm takes much less time than the first "programmers".

At the beginning of the 19th century, the French weaver and inventor Joseph-Marie Jacquard invented a new technology for industrial patterning of fabrics. Now such fabrics are called jacquard, and his machine - jacquard. Jacquard's invention makes it possible to obtain a variety of lighting effects on the surface of the fabric, and in combination with different colors and material of the threads, beautiful, soft transitions of tones and sharply defined contours of patterns, sometimes very complex (ornaments, landscapes, portraits, etc.). Jacquard is used for sewing dresses, outerwear, furniture fabrics, curtains, as well as for the manufacture of lanyards, badge tapes and other promotional materials (stripes, chevrons, labels, promotions).

Joseph Jacquard was born on July 7, 1752. in Lyon. His father owned a small family weaving industry (two looms), and Joseph also began his career as a child at one of the many weaving factories in Lyon. But this hard and unsafe work did not appeal to him, and the future inventor went to study and work in a bookbinding workshop.

But Jacquard was not destined to become an outstanding inventor in bookbinding or printing. Soon, his parents die, and he inherits looms and a small piece of land. As a result of several unsuccessful business projects, Joseph loses most of his father’s inheritance, but at the same time he is fond of the engineering problem of improving the loom.

Despite the rapid development of weaving in France, the possibilities themselves  looms were very limited. Monochrome fabrics or colored stripes were produced in droves. Fabrics with embroidered patterns were still made by hand. Jacquard wanted to improve the loom so that it was possible to make patterned fabrics in an industrial way.

looms were very limited. Monochrome fabrics or colored stripes were produced in droves. Fabrics with embroidered patterns were still made by hand. Jacquard wanted to improve the loom so that it was possible to make patterned fabrics in an industrial way.

By 1790, Jacquard created a prototype of the machine, but active participation in revolutionary events in France did not allow him to continue working on improving his invention. After the revolution, Jacquard continued his design searches in a different direction. He invented a machine for weaving nets and in 1801 he took him to an exhibition in Paris. There, he saw Jacques de Vaucanson's loom, which back in 1745 used a perforated roll of paper to control the weaving of threads. What he saw prompted Jacquard to a brilliant idea, which he successfully used in his loom.

To manage each thread individually, Jacquard came up with a punched card and an ingenious mechanism for reading information from it. This made it possible to weave fabrics with patterns predefined on the punch card. In 1804, the invention of Jacquard received a gold medal at the Paris exhibition, and he was granted a corresponding patent. The final industrial version of the jacquard machine was ready by 1807.

In 1808, Napoleon I awarded Jacquard a prize of 3,000 francs and a right to a prize of 50 francs each  operating in France machine of its design. By 1812, more than ten thousand jacquard looms worked in France. In 1819, Jacquard received the Cross of the Legion of Honor.

operating in France machine of its design. By 1812, more than ten thousand jacquard looms worked in France. In 1819, Jacquard received the Cross of the Legion of Honor.

Joseph Marie Jacquard died in 1834 at the age of 82. In Lyon in 1840, a monument was erected to him. The Jacquard loom allowed not only industrial weaving of fabrics with complex patterns (jacquard), but also became the prototype of modern automatic looms.

The Jacquard machine is the first machine to use a punch card in its work.

Already in 1823, the English scientist Charles Babaj tried to build a computer using punch cards. At the end of the 19th century, an American scientist built a computer and processed the results of the 1890 population census on it. Punched cards in computer technology were used until the middle of the twentieth century.

(decorative fabrics, carpets, tablecloths, etc.). It makes it possible to separately manage each thread of the warp or a small group of them. Created in 1804.

Encyclopedic YouTube

1 / 3

✪ Jacquard - LIVE, China

✪ DORNIER jacquard loom

✪ Picanol looms

Subtitles

History

Named after the French weaver and inventor Joseph Marie Jacquard.

Application

The jacquard machine makes it possible, when a pharynx is formed on a loom, to separately control the movement of each thread or a small group of warp threads and to produce fabrics whose rapport consists of a large number of threads. Using a jacquard machine, it is possible to produce patterned dress and decorative fabrics, carpets, tablecloths, etc.

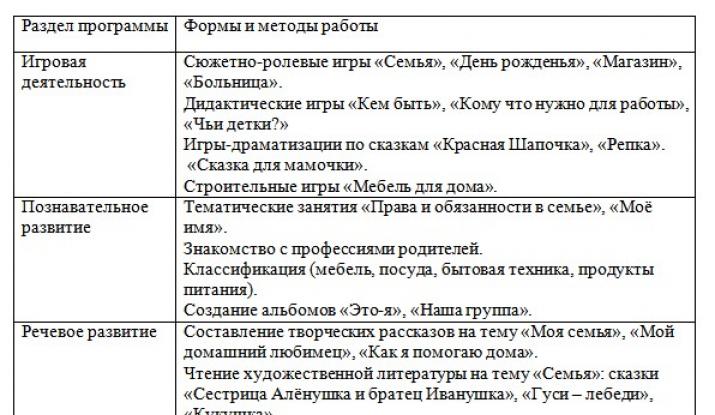

Description

The jacquard machine has knives, hooks, needles, a plank, frame cords and a perforated prism. The warp threads, made into the eyes of persons (galevs), are connected to the machine using arcade cords threaded into a dividing board for uniform distribution along the width of the machine. Knives fixed in a knife frame reciprocate in a vertical plane. The hooks located in the area of \u200b\u200baction of the knives are grabbed by them and rise upwards, and the warp threads rise upwards through the frame and arcade cords, forming the upper part of the throat (the main overlap in the fabric). Hooks brought out of the range of the knives are lowered down along with the frame board. The lowering of hooks and warp threads occurs under the influence of gravity weights. The lowered warp threads form the lower part of the pharynx (weft weaves in the fabric). Hooks from the area of \u200b\u200baction of the knives are displayed with needles, which are affected by a prism having oscillating and rotational movements. A cardboard is made up of a prism, consisting of individual paper cards that have cut-out and not-cut places against the ends of the needles. Meeting the cut-out place, the needle enters the prism, and the hook remains in the area of \u200b\u200bthe knife’s action, and the not-cut place of the card moves the needle and disconnects the hook from the interaction with the knife. The combination of the cut and not cut places on the cards allows for a quite definite alternation of raising and lowering the warp threads and the formation of a pattern on the fabric.

A striking example of a computer-controlled machine, created long before the advent of computers. The punched card is typed in a binary code: there is a hole, there is no hole. Accordingly, some thread rose, some did not. The shuttle throws a thread into the formed pharynx, forming a two-sided ornament, where one side is a color or texture negative of the other. Since to create even a small-sized pattern, about 100 or more weft threads and an even larger number of warp threads are required, a huge number of perforated cards were created, which were connected into a single ribbon. Scrolling, she could occupy two floors. One punched card corresponds to one procid shuttle.

Jacquard fabric

coarse fabrics of any kind of fiber produced on jacquard looms and going to the production of bedspreads, tablecloths, etc .; named J.M. Jacquard.

Joseph Marie Jacquard

Joseph Marie Jacquard (1752–1834)

french inventor. Born in Lyon in the family of a silk spinner. He inherited a small workshop from his father, but soon went bankrupt. In 1790, the goal was to restore the loom built 50 years earlier by Jacques de Vaucazan. It was one of the first examples of an automatic loom. The French Revolution temporarily interrupted the work of Jacquard. He fought in the ranks of the Republican army, but after the victory he set to work again. In 1801 he designed the machine, for the control of which punch cards were used; later he improved the machine by combining punch cards into an endless ribbon, which made it possible to weave large canvases and carpets. The French government became interested in the invention. Jacquard began to pay money for every loom made of his design. In 1812, 11 thousand Jacquard machines were operating in France. They began to appear in other countries. The use of automatic looms in 1820 caused a textile boom in Europe.

Subsequently, Charles Babbage used punched cards similar to those used by Jacquard in order to create an automatic counting device.

see also Ada.

safety Shaving Blade, the world's first disposable product. The name is named after K.K. Gillette.

King Camp Gillette

King camp gillette

american inventor and entrepreneur. Born in Font du Lac (Wisconsin). In 1871, his family lost all their property in a big fire in Chicago. Gillette was forced to become a salesman, selling hardware. While sharpening the blade of a dangerous razor, he came up with a safe replaceable blade (a steel plate with two sharp edges) and a safety razor (a clip of this blade equipped with a handle). The invention was met with skepticism - after all, the blades could not be re-sharpened. In 1903, only 51 razors and 168 blades were sold, but by the end of 1904, 90 thousand razors and 12 million 400 thousand blades. Until 1931, Gillette was president of the company he created for the production of razor blades, and left real management in 1913, devoting himself to promoting his social views. He was a Utopian socialist, author of several books and articles; believed that competition was wasteful, and called for the creation of a planned society controlled by technocrats. In 1910, he unsuccessfully offered US President Theodore Roosevelt to create a "global corporation" in Arizona (which had not yet become the US state) and become its president. Gillette himself agreed to allocate $ 1 million for this endeavor.

For many years, punched cards served as the main carriers for storing and processing information. In our minds, a punch card is firmly associated with a computer occupying an entire room, and with a heroic Soviet scientist making a breakthrough in science. Punch cards - the ancestors of floppy disks, disks, hard drives, flash memory. But they did not appear at all with the invention of the first computers, but much earlier, at the very beginning of the 19th century ...

Falcon's machine tool Jean-Baptiste Falcon created his machine on the basis of the first such machine designed by Basil Bouchon. He was the first to invent a system of cardboard punch cards connected in a chain.

Alexander Petrov

On April 12, 1805, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and his wife visited Lyon. The country's largest weaving center in the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries was badly damaged by the Revolution and was in a deplorable state. Most factories went bankrupt, production stood still, and the international market was increasingly filled with English textiles. Wanting to support the Lyon masters, in 1804 Napoleon placed a large order for cloth here, and a year later he arrived in the city personally. During the visit, the emperor visited the workshop of a certain Joseph Jacquard, the inventor, where the emperor was shown an amazing machine. The masses mounted on top of an ordinary loom tinkled with a long ribbon of perforated tin plates, and a silk cloth with an exquisite pattern stretched, spinning onto a shaft. At the same time, no master was required: the machine worked on its own, and even an apprentice could well serve it, as the emperor was explained.

1728. Falcon machine. Jean-Baptiste Falcon created his car on the basis of the first such machine designed by Basil Bouchon. He was the first to invent a system of cardboard punch cards connected in a chain.

1728. Falcon machine. Jean-Baptiste Falcon created his car on the basis of the first such machine designed by Basil Bouchon. He was the first to invent a system of cardboard punch cards connected in a chain.

Napoleon liked the car. A few days later, he ordered the transfer of Jacquard's patent for a weaving machine to the public, and the inventor himself to put an annual pension of 3,000 francs and the right to receive a small, 50 francs, deduction from each loom in France on which his car was parked. However, as a result, this deduction amounted to a significant amount - by 1812, 18,000 looms were equipped with a new device, and in 1825 - already 30,000.

The inventor lived the rest of the days in abundance, he died in 1834, and six years later, the grateful citizens of Lyon erected a monument to Jacquard in the very place where his workshop had once been. Zhakkarova (or, in the old transcription, “jacquard”) the car was an important brick in the foundation of the industrial revolution, no less important than the railway or steam boiler. But not everything in this story is simple and cloudless. For example, the "grateful" Lyons, who later honored Jacquard as a monument, broke his first unfinished machine tool and attempted his life several times. And the truth is that he didn’t invent the car at all.

1900. Weaving shop. This picture was taken more than a century ago in the factory floor of a weaving mill in Darwell (East Ayrshire, Scotland). Many weaving shops look like this to this day - not because the factory owners spare money for modernization, but because the jacquard looms of those years are still the most versatile and convenient.

1900. Weaving shop. This picture was taken more than a century ago in the factory floor of a weaving mill in Darwell (East Ayrshire, Scotland). Many weaving shops look like this to this day - not because the factory owners spare money for modernization, but because the jacquard looms of those years are still the most versatile and convenient.

How the car worked

To understand the revolutionary novelty of the invention, it is necessary in general terms to present the principle of operation of a loom. If you look at the fabric, you can see that it consists of tightly interwoven longitudinal and transverse threads. In the manufacturing process, longitudinal threads (warp) are stretched along the machine; half of them are attached to the “remise” frame through one, the other half to the same frame. These two frames move up and down relative to each other, spreading the warp threads, and the shuttle pulling the transverse thread (ducks) back and forth into the formed pharynx. The result is a simple canvas with threads interwoven through one. The frame-remizok can be more than two, and they can move in a complex sequence, raising or lowering the threads in groups, which is why a pattern forms on the surface of the fabric. But the number of frames is still small, rarely when it is more than 32, so the pattern is simple, regularly repeating.

There are no frames at all on the jacquard loom. Each thread can be moved separately from the others with the help of its rod with a ring. Therefore, on the canvas you can weave a pattern of any degree of complexity, even a picture. The sequence of movement of the threads is set using a long looped card punch card, each card corresponds to one shuttle pass. The card is pressed to the "reading" wire probes, some of them go into the holes and remain stationary, the rest are recessed with the card down. The probes are connected to the rods that control the movement of the threads.

Complicated canvases knew how to weave before Jacquard, but only the best masters could do it, and the work was hellish. A jerking worker climbed inside the machine and, at the command of the master, manually lifted or lowered individual warp threads, sometimes hundreds of them in number. The process was very slow, required constant attention, and errors inevitably occurred. In addition, the re-equipment of the machine from one complexed canvas to another work sometimes stretched for many days. The machine tool of Jacquard did the work quickly, without errors - and himself. The only difficult thing now was to fill in punch cards. It took weeks to produce one set, but once produced cards could be used again and again.

Predecessors

As already mentioned, the "smart machine" was not invented by Jacquard - he only modified the inventions of his predecessors. In 1725, a quarter of a century before the birth of Joseph Jacquard, the first such device was created by the Lyon weaver Basil Bouchon. Bushon's machine was controlled by perforated paper tape, where each row of the shuttle corresponded with one row of holes. However, there were few holes, so the device changed the position of only a small number of individual threads.

The next inventor who tried to perfect the loom was called Jean-Baptiste Falcon. He replaced the tape with small sheets of cardboard tied around corners in a chain; on each sheet, the holes were already arranged in several rows and could control a large number of threads. The Falcon machine was more successful than the previous one, and although it was not widely used, the master managed to sell about 40 copies throughout his life.

The third person who undertook to bring the loom to mind was the inventor Jacques de Vaucanson, who in 1741 was appointed inspector of silk weaving factories. Vaucanson worked on his machine for many years, but his invention was unsuccessful: a device too complex and expensive to manufacture could still control a relatively small number of threads, and a plain fabric did not pay for the cost of the equipment.

1841. Weaving workshop of Karkill. A woven pattern (made in 1844) depicts a scene that occurred on August 24, 1841. Monsieur Karkilla, the owner of the workshop, presents to the Duke d'Omale the canvas with a portrait of Joseph Marie Jacquard, woven in the same way in 1839. The subtlety of the work is incredible: the details are smaller than on engravings.

1841. Weaving workshop of Karkill. A woven pattern (made in 1844) depicts a scene that occurred on August 24, 1841. Monsieur Karkilla, the owner of the workshop, presents to the Duke d'Omale the canvas with a portrait of Joseph Marie Jacquard, woven in the same way in 1839. The subtlety of the work is incredible: the details are smaller than on engravings.

Good luck and failures of Joseph Jacquard

Joseph Marie Jacquard was born in 1752 on the outskirts of Lyon in a family of hereditary Canuts - weavers who worked with silk. He was trained in all the intricacies of the craft, helped his father in the workshop, and after the death of his parent inherited the matter, but he was far from engaged in weaving. Joseph managed to change many professions, was tried for debt, married, and after the siege of Lyon he left as a soldier with a revolutionary army, taking his sixteen-year-old son with him. And only after the son died in one of the battles, Jacquard decided to return to the family affair.

He returned to Lyon and opened a weaving workshop. However, the business was not very successful, and Jacquard became interested in invention. He decided to make a machine that would surpass the creations of Bouchon and Falcon, would be quite simple and cheap, and at the same time could make a silk canvas, not inferior in quality to a hand-woven. At first, the designs that came out from under his hands were not very successful. The first Jacquard machine, which worked as it should, did not make silk, but ... fishing nets. In the newspaper, he read that the Royal Royal Society for the Support of the Arts had announced a competition for the manufacture of such a device. He never received a prize from the British, but he was interested in his brainchild in France and was even invited to an industrial exhibition in Paris. It was a landmark trip. Firstly, they paid attention to Jacquard, he got the necessary connections and even got money for further research, and secondly, he visited the Museum of Arts and Crafts, where Jacques de Vaucanson's loom was located. Jacquard saw him, and the missing details fell into place in his imagination: he understood how his car should work.

With his developments, Jacquard attracted the attention of not only Parisian academics. Lyon weavers quickly realized the threat posed by the new invention. In Lyon, whose population was barely 100,000 by the beginning of the 19th century, more than 30,000 people worked in the weaving industry - that is, every third resident of the city was, if not a master, then an employee or an apprentice at a weaving workshop. An attempt to simplify the fabrication process would have deprived many of the work.

The incredible precision of the Jacquard machine

The famous painting “The visit of the Duke of O'Mal to the weaving workshop of Mr. Karkill” is not an engraving at all, as it might seem, - the picture is completely woven on a machine equipped with a jacquard machine. Canvas size - 109 x 87 cm, the work was done, in fact, by the master Michel-Marie Karkilla for the company Didier, Petit and Sea. The process of mis en carte - or programming the image on punch cards - lasted many months, with several people doing it, and the production of the canvas took 8 hours. A tape of 24,000 (more than 1,000 binary cells each) punch cards was a mile long. The picture was reproduced only by special orders; several canvases of this type are known that are stored in various museums around the world. And one portrait of Jacquard so woven in this way was commissioned by Charles Babbage, Dean of the Department of Mathematics, University of Cambridge. By the way, the duke d'Omal depicted on the canvas is none other than the youngest son of the last king of France, Louis Philippe I.

As a result, one beautiful morning a crowd came to the workshop of Jacquard and broke everything that he was building. The inventor himself was severely punished to leave unkind and engage in craft, following the example of his late father. Contrary to the exhortations of the brothers in the workshop, Jacquard did not give up his research, but now he had to work secretly, and he finished the next car only by 1804. Jacquard received a patent and even a medal, but he was careful not to sell smart machines on his own, and on the advice of the merchant Gabriel Detille, he asked the emperor to transfer the invention into the public ownership of the city of Lyon. The emperor granted the request, and awarded the inventor. You know the ending of the story.

Punch Card Age

The very principle of the jacquard machine - the ability to change the sequence of the machine by loading new cards into it - was revolutionary. Now we call it the word "programming." The sequence of actions for the jacquard machine was set in a binary sequence: there is a hole - there is no hole.

1824. Difference machine. Babbage The first experience with Charles Babbage's construction of an analytical machine was unsuccessful. The bulky mechanical device, which is a combination of shafts and gears, calculated quite accurately, but required too complicated maintenance and highly skilled operator.

1824. Difference machine. Babbage The first experience with Charles Babbage's construction of an analytical machine was unsuccessful. The bulky mechanical device, which is a combination of shafts and gears, calculated quite accurately, but required too complicated maintenance and highly skilled operator.

Soon after the jacquard machine became widespread, perforated cards (as well as perforated tapes and discs) began to be used in a variety of devices.

Shuttle machine

At the beginning of the XIX century, the main type of automatic weaving device was a shuttle machine. It was arranged quite simply: warp threads were stretched vertically, and a bullet-shaped shuttle flew between them back and forth, dragging a transverse (weft) thread through the warp. From time immemorial the shuttle was dragged by hands, in the XVIII century this process was automated; the shuttle "shot" on one side, was accepted on the other, unfolded - and the process repeated. The pharynx (the distance between the warp threads) for the shuttle span was provided with the help of a bird-weaving ridge, which separated one part of the warp threads from the other and lifted it.

But perhaps the most famous of these inventions - and the most significant on the way from the loom to the computer - is the "analytical machine" of Charles Babbage. In 1834, Babbage, a mathematician inspired by Jacquard's experience with punch cards, began work on an automatic device to perform a wide range of mathematical problems. Prior to that, he had a bad experience building a “difference machine,” a bulky 14-ton monster filled with gears; The principle of processing digital data using gears has been used since Pascal's time, and now punch cards should replace them.

1890. The tabulator of Holleritis. Herman Hollerith's tabulating machine was built to process the results of the 1890 All-American Census. But it turned out that the capabilities of the machine go far beyond the scope of the task.

1890. The tabulator of Holleritis. Herman Hollerith's tabulating machine was built to process the results of the 1890 All-American Census. But it turned out that the capabilities of the machine go far beyond the scope of the task.

The analytical machine contained everything that exists in a modern computer: a processor for performing mathematical operations ("mill"), memory ("warehouse"), where the values \u200b\u200bof variables and intermediate results of operations were stored, there was a central control device that also performed input functions output. Two types of punch cards were to be used in the analytical machine: large format, for storing numbers, and smaller - software. Babbage worked on his invention for 17 years, but could not finish it - there was not enough money. The current model of Babbage’s “analytical machine” was built only in 1906, so the direct predecessor of computers was not she, but devices called tabulators.

A tabulator is a machine for processing large amounts of statistical information, textual and digital; information was entered into the tab using a huge number of punched cards. The first tabulators were designed and created for the needs of the American census office, but soon they were used to solve a variety of problems. From the very beginning, one of the leaders in this field was the company of Herman Hollerith, the man who invented and manufactured the first electronic tabulation machine in 1890. In 1924, Hollerita was renamed IBM.

When the first computers replaced the tabs, the principle of control using punch cards remained here. It was much more convenient to load data and programs into the machine using cards, rather than switching numerous toggle switches. Here and there punch cards are used to this day. Thus, for almost 200 years, the main language in which a person spoke with “smart” machines remained the language of punch cards.

The article “Loom, great-grandfather of computers” was published in the journal Popular Mechanics (